Accelerating Learning

we cannot shortcut the process of accumulating knowledge and skills over the long term. But as we learn how to learn, we discover that some methods of learning are better than others.

We all wish we could learn more quickly. As managers we wish we could accelerate the learning of our teams. In some ways, we cannot shortcut the process of accumulating knowledge and skills over the long term. But as we learn how to learn, we discover that some methods of learning are better than others.

Someone recently asked why engineers should earn more than teachers. My reply was that the two are not mutually exclusive. In fact, any great engineering manager is also a great teacher. A manager is only as good as their ability to teach their team. We can take this a step further to say that the best learners do not passively get taught. Most learning is self-learning. The better we can teach ourselves, the better we learn.

An old proverb goes something like this, "Tell me and I forget, teach me and I may remember, involve me and I learn." Some medical schools use the method of SODOTO, “See One, Do One, Teach One.” If we delve deeply into this and expand upon it, we have a framework, not just for learning a concept but for accelerating the achievement of mastery.

See One

You start with observing the right approach to what you want to learn. This could be an expert demonstrating a skill, the prevailing theory on the optimal approach, or a story of what worked. As humans, we have added to our collective wisdom from generation to generation by passing along knowledge through story. Stories make powerful connections to us as we learn vicariously through the experiences of others. This is good for understanding what to do, but not necessarily how or why it was developed.

If we are going to go beyond what is considered the best, we need to be able to advance the theory. To do this, we want to know how we arrived at the theory. Anyone who learns the complete history of the topic holds the advantage. William Duggan delves into this in his book, The Art of What Works. Researching lessons from history gives us insight into what has worked for others in the past.

Napoleon became one of the most successful generals in history because of his extensive knowledge of the history of warfare. Later Patton took his knowledge of the history of warfare to another level. When the Wright Brothers decided to try to achieve heavier-than-air flight for humans, they started by researching everything they could find on the history of flight.

When Jeffrey Katzenberg went to work at Disney in the 1980s, he discovered the archives that Walt Disney kept on making movies and telling stories. He began to stay up at night to absorb all he could and started applying what he learned to the films that rejuvenated the Disney brand such as The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, and The Lion King. I highly recommend the book Disney War by James B. Stewart.

Barry Diller, former CEO of Paramount Pictures and 20th Century Fox, started his career in the William Morris Agency when he discovered their archives. He spent three years devouring what was essentially the history of the film industry, which gave him an edge over anyone else his age.

When I made the career leap from financial services to manufacturing, I decided to learn everything I could about the history of quality. That’s how I discovered Walter Shewhart, W. Edwards Deming, Joseph Juran, and Taichi Ohno, some of the people most responsible for the most important advancement in management during the 20th century – the quality revolution. I thought I was going to learn about quality, and I ended up learning about management.

Every year I read business biographies, listen to business podcasts, and watch business documentaries. I also read business theory to give myself some basis for interpreting all the stories I absorb. All these stories help me weed out a lot of the bad advice that is available. The stories also help me communicate tips and techniques to my team because I can readily give compelling examples of others who have used those techniques to great success.

I will add that one of the best ways I have found to enhance the See One stage is to take notes. I find that taking notes with a pen and notebook works far better than electronic notes. When I have a conversation with a client on the phone, I will take notes directly into our CRM rather than have to spend the extra time transcribing later. When I am in learning mode, I prefer a physical notebook or journal. For some reason, this seems to give me a closer connection to what I am writing, so I can better absorb and remember later.

Notebooks seemed to be far more common in the past than they are today. Leonardo da Vinci, Ben Franklin, Albert Einstein, and Walter Chrysler all kept notebooks. When I was 12, I read the biography of Robert Louis Stephenson, and learned that he carried a notebook in his pocket, so I started keeping a notebook ever since.

Do One

In this stage, you put what you learned into practice. Management and many of the microskills that make up management are not learnable through books alone. You must experience the thoughts, feelings, and distractions that come along with doing. Learning negotiation by reading a book is different from feeling the adrenaline rush and shaking hands that come with going through a high-stakes negotiation where the pressure is on while the level of agreement and certainty are low.

One of the best reasons to do is to better deal with the real pressure that comes along with doing. I love to watch the Olympics because these people have spent years preparing for an opportunity that comes only once every four years and may never come along again for the rest of their lives. The future path of their lives comes down to a few minutes of performance, so the pressure is high, and some can deal with it while others crumble under the pressure. I think back to this when I feel the pressure rising in my life, and I welcome the pressure.

Doing is about experimentation. Experimentation is also about improvement. As a runner, I read about techniques, but until I do them I do not actually know how they feel. I have to do it, feel it, and then get some sort of feedback that validates that this sensation equates to the optimal technique.

Teach One

I really learn when I teach. You could say that I learned this the hard way. The point in my life when I hit rock bottom was when I was 20 and living in New York City with no job and $50 left in my pocket. My parents were living in their van traveling the country, and I had no idea how to contact them. During the end of that cold December I had walked into one retailer after another to fill out job applications, but everybody was winding down from the holidays and more likely to be laying off than hiring.

I spoke to a friend who had directed one of the plays in which I had acted, and he told me about a teaching position at the high school where he taught. It was for Algebra, Geometry, Earth Science, Biology, and Physics. The other teacher had left halfway through the year, and they needed somebody.

A million reasons why I couldn’t do it raced through my head. “But I don’t have a teaching license.” Apparently, that was not a requirement because it was a private high school. “But I don’t have a degree.” He said that didn’t matter because I did graduate from an acting conservatory. “But I never took Physics before in my life.” He said they wouldn’t care.

If I had any other option, I never would have thrown my hat into the ring. I had been eating less to save money, and my insecurity level was high. But I was desperate (and hungry). I got an interview, and I was honest about myself. He said I got the job. They must have had no other options either. I had always loved math, and I had found science to be very intriguing, but I was far from being able to teach the subjects and far from being qualified to stand before some kids who were only a few years younger and portray myself as an expert.

On the first day, I tried to hide the fact that I was in my panic zone. Did I mention that this was an all-boys school? Oh, yes, the energy level was high. They were polite to the other teachers who were older and wiser. But they were so rowdy with me that the principal made regular visits into my class. As soon as he would enter, they would quiet down. I survived the first day. One day they asked me what pH stands for. I had to look it up in the book, and somebody complained to the principal that I had to look it up in the book, so he had a talk with me about that. Then I survived the first week. Then I survived the first month. Each night, I would study the lesson for the next day.

In the beginning I had been spending a lot of time learning the topic where I had to be an expert. I had tried repetition to learn and practiced like I would practice lines as an actor. Then about a month into this experience something crazy happened. As the weeks passed, that process compressed, and I jumped straight from getting introduced to a new topic to immediately teaching that topic. I had just read something in physics, and realized I felt like an expert even though I had never known about that topic only a few minutes earlier. This sparked a self-learning technique that I still use to this day.

What did I do? I read it once to get a general introduction to the idea as if it were someone else’s words. Then I read it a second time as though they were my own words, and I was trying to explain it to someone else.

This is a variation on an acting technique. I had once taken an acting class with Alan Arkin who told us to first read the script with no preconceived notions. In other words, read it first with an open mind. Just take in the information in an accepting way. Then you make the words your own.

Now when I come across something I like and want to absorb as a part of my learning, I repeat it in my head as if I am teaching someone else.

If we are all learning, we are all teachers because we teach ourselves, and as we develop, we pass along our knowledge and skills onto others. That is how we connect with others and contribute to our collective advancement. We owe our knowledge and abilities today, in large part, to the discoveries others have made and passed along to us. Our responsibility is to learn from our history, improve upon it, and pass it along for the next generation. If we can accelerate not only our own learning but also the next generation’s learning, we can accelerate our collective learning.

How to Coach Your Team into the Learning Zone

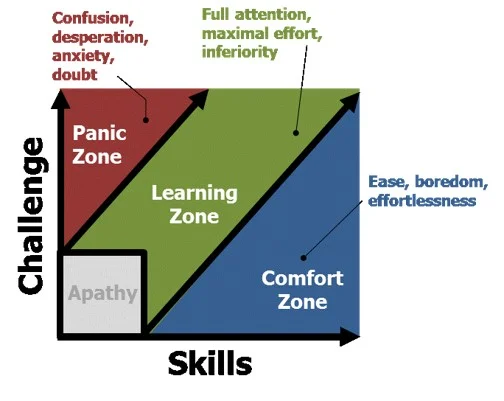

Real growth and improvement happens, not in your Comfort Zone but in your Learning Zone. Your team needs to know that the discomfort of growth and development is a good thing.

Last summer when we took a family vacation at a kid-friendly resort, I looked around the lazy river, pool, and slides and noticed that every child was running around while every adult was either sitting or lying down. I told my brother-in-law that was the reason why the kids were in far better shape than the adults. As a result, in some micro way, the kids were growing while the adults were deteriorating. The kids were actively playing in a way that constantly pushed themselves to explore new limits, triggering growth in their bodies and brains. By contrast the adults were looking for their Comfort Zone.

Real growth and improvement happens, not in your Comfort Zone but in your Learning Zone. I have previously written about the Learning Zone here. This is about cultivating skills. The companies which learn and improve more rapidly improve their odds of surviving and thriving. If you want a company that engages in continual improvement, you need a team of continual learners. That means your team needs to enter the Learning Zone. This is an uncomfortable place to be. Going into the Learning Zone exposes you to disappointment, insecurity, pain, failure, and loss. It can contradict the goals you have established for happiness, the easy life, and safety.

After reading Daniel Coyle’s book “The Talent Code”, I started looking at the world in a new way. Where I used to see habits or preferences, I started seeing skills which were either developed or undeveloped. Many problems and challenges can be related back to skills. I used to be skilled at eating ice cream. When I was a vegetarian, I was skilled at avoiding red meat. I used to be unskilled at waking up at 5AM every day, but with practice over time I have grown quite skilled at awakening early.

We cannot un-practice skills we no longer want. We can only practice new skills we do want. This type of practice is called deliberate practice or deep practice. We only truly engage in deliberate practice when we enter our Learning Zone.

I recently completed my fifth New York City marathon. When I started running as an adult, I just pounded my feet on the pavement with no technique. That is like hitting my fists on piano keys and claiming I could play the piano. The proper training puts me in my Learning Zone. Over time my body has made changes I never imagined or expected. Since childhood I struggled with asthma, and once while travelling in southeast Asia, I was afraid to go to sleep because I thought might not wake up. I started running again as an adult, and now I have gone 11 years with no breathing issues. I have more energy. I feel more connected to my body. This concept has made me a healthier person, a better father, and a better manager.

What can you do as a manager to get your team into their Learning Zone? In short, you want to treat the Learning Zone as a skill they will develop. Share the Learning Zone model with them so they understand it, connect the theory to their real-world situations, and motivate them frequently over the long term.

What is the Learning Zone?

People need to know that the discomfort of growth and development is a good thing. Some part of our nature rejects what is uncomfortable and unknown because of the associated danger. We need some guidance on discerning good discomfort from bad discomfort.

The most powerful tool I have found in getting people into their Learning Zone was to show them what the Learning Zone is. What is the Learning Zone? The Learning Zone is, by definition, not the Comfort Zone. It is not easy. It requires your full attention and effort. It is a mental struggle. It can be an emotional struggle. It is sometimes even a physical struggle. Why? That struggle initiates the message in your brain that you need to improve in some way.

The Learning Zone is a sweet spot to hit somewhere after you leave your Comfort Zone and before you hit your Panic Zone. This will depend upon how much skill you have and how great the challenge is. As you develop the skill, you will require greater challenges to hit your Learning Zone.

How many words per minute can you type? That depends in large part upon how many hours of deliberate practice you put into developing the skill. That holds true for any skill. A signal for a task you have never done before might move through your brain at two miles per hour. The signal for a task you have practiced for years could travel through your brain at 200 miles per hour. I share this video with the team, so they understand this.

Now when I run, I focus on my technique and the subtle adjustments necessary to improve my technique. I do not read, watch television, or listen to music while I run because those distract me from improving my technique. I see runners in the park with headphones and at the gym watching television. Are they focusing full attention on improving their technique, or are they distracted?

This mental model is an easy-to-remember visual which helps people understand that being uncomfortable is a good thing because that is where they learn and grow the most. When I show them the model, I like to share some examples of times when I was in my Learning Zone and times when I was in my Panic Zone.

Then I like to talk about moving among the zones. The idea is to develop two skills. The first skill is that transition from Comfort Zone to Learning Zone. The feeling of moving from the Comfort Zone into the Learning Zone can feel quite wrong even though it is quite right. The second skill is the ability to move from the Panic Zone back into the Learning Zone. Again, I share examples of doing this. I was once coaching someone through an important negotiation and could tell they were in their Panic Zone. They took a break and went for a five-minute walk outside to pull back into the Learning Zone. I find vigorous exercise helps pull me back. In both cases, practice helps improve these skills over time.

Bridge the Gap

Once your team understands what the Learning Zone is and why it is important, you must help them build their ability to go into their Learning Zone. To do this you will help them bridge the gap between the concept and their own personal experiences. I start by asking questions: When were you in your Learning Zone? When were you in your Panic Zone? Where are you now? Asking this question on a regular basis helps get them thinking about it more and they get better at assessing their current state.

If they are bored, they are in their Comfort Zone, which means you, as their manager, are not providing enough challenges for them. This is important feedback for you. My daughter’s elementary school, like many now, gives books and reading assignments based upon the child’s reading level. This helps ensure they are reading at the appropriate level, like the way music, martial arts, and many other skills are taught. Unfortunately, math and science are not yet taught this way, but in time they most likely will be.

If your team says they are overwhelmed and stressed out, they are in their Panic Zone. Learning is far less likely to happen with intense levels of fear and other emotional distractions. The quick fix is to reduce the challenge level. The long-term solution is to increase the skill level. As I gained more responsibility in my career and life, the level of pressure, uncertainty, stakes, and disagreement grew. Sometimes an increase would feel like too much at first, but as I learned to deal with it and went on to the next level, what once felt unbearable later felt like a walk in the park.

In general, you want to frame the journey as a small continuation of what is already being done. I took some improvisation classes at The Upright Citizens Brigade where we had to practice “Yes and…” exercises. The idea was to continue the flow and direction that others were going. The idea is to build a joint momentum together. I once had a director who was expert at framing instructions as “Do more of that.” In the movie Stand and Deliver, real-life high-school math teacher Jaime Escalante told his drop-out prone students that math is in their blood because their Mayan ancestors came up with the concept of zero when the Greeks and Romans could not.

Motivate your Team

As much as possible, you want to get people excited about going into the Learning Zone. Motivation is less about giving long speeches or imposing incentives or consequences and more about connecting with other people, making meaningful contributions, and gratification when unexpected accomplishments are achieved.

People connect with other people through the power of story. Filling the mind with stories of examples from history of people who have achieved success is a reliable source of inspiration. When my four-year-old son watched Rocky, he pretty much spent the entire movie working out. As a manager, my tactic is to keep sharing one story after another week after week of people who went into their Learning Zone and built up their skills. I have shared hundreds of stories and dozens of videos with my team, such as this, this, this, this, and this.

People are motivated by the ability to make unique and meaningful contributions. If you had a unique skill that nobody cared about, you would have less motivation than you would if you discovered that skill was a huge benefit to a lot of people. When I am relieved to have somebody on the team who makes a meaningful contribution because they have some skill I do not have, I make sure to acknowledge their contribution, express appreciation, and remind them that I am relieved to have them because they are able to do something I cannot.

Gratification is the sense of accomplishment which is intensified by the difficulty in getting there. When times get challenging, I remind the team about where we are going and how great we will feel when we get there. I love to use the analogy of climbing Everest. The journey is miserable, but the payoff is great, in part because of all the suffering along the way. If the whole process were easy, the end would not bring the same sense of accomplishment.

When I was young, my parents taught me that when we are ready to stop learning, we are ready to move on toward dying. I recently heard that a long life is less dependent upon a low-stress life and more dependent upon how engaged we are. This is easy to believe because when we engage our efforts, our brains and bodies respond with some sort of growth. We used to believe that our capacity to learn diminished as we age, but that belief has been debunked. Our brains are extremely adaptive, and some parts of the brain will expand or contract depending upon what we are learning even as adults.

My parting message to you on this topic is that as a manager, you lead by example so step into your Learning Zone on a regular basis. Do it in new and unexpected ways. Share your genuine challenges with your team. This has the added benefit of expressing your vulnerability, which deepens your connections with others and makes for a stronger team.

Climbing the Ladder of Accountability

Where are you on the Ladder of Accountability? Where is your team?

"Where does that put you on the Ladder of Accountability, David?" Did one of my employees just catch me being low on the Ladder of Accountability after I had been preaching accountability for over a year? Yep. The student was now teaching the teacher. We had reached a major milestone. The endless repetition of that same message was starting to pay off. Then people started questioning each other about the Ladder of Accountability.

The year before we had suffered from a victim culture, so I had created a graphic with a four-rung ladder displaying the four levels of accountability. I didn’t invent the Ladder of Accountability. I just tweaked it. Then I shared it with the team. The research had shown the high cost of a low-accountability team, but we didn’t even need that because we could tell it was costing us, and we had to do something about it, or it would just get worse as we grew as a company.

We all started talking about it regularly and explored this new way of looking at our interactions with each other. Our CEO had printed out the ladder, and when an employee came to complain to him, the CEO pointed to the printout and asked him where he was on the Ladder of Accountability. That woke up the employee. Later in the same conversation, the same employee started to say something that would have been low accountability, and he stopped himself. He thought of how to think differently, and they shared a laugh. When an employee would come to me to tell me about an issue, my first question would be, "What do you suggest?" Some people loved this question because it showed their opinions and contributions were valued. Others hated the question because it meant they had more responsibility, more work, and more mental effort. These are the people who love to put the monkey on their manager's back.

We had to struggle to implement the change. We treated accountability as a skill. Just like any skill it requires practice. Practice involves intense struggle. We had to work together to understand what accountability means and practice together to be able to do it. Sometimes people had situations but were uncertain what action would be high on the Ladder, so we would talk it through together. At other times people thought they were taking the accountable action when they were not. In certain cases, we would look back and think we erred on the side of being too accountable, but ultimately that never turned out to be true.

I cannot say when the shift happened exactly, but at some point, we had absorbed the value of accountability so deeply that new people needed less training on it because they just saw how things are done and fell into line with that. They had no idea what kind of mental and emotional struggle we had undergone as a company to develop our accountability. Some people who were low on the Ladder just would not make the changes necessary, and decided to leave. We even interviewed new candidates who decided to withdraw their application because high accountability just did not interest them. Today an outsider might see and feel the norms of the group and understand what is acceptable without even being able to place their finger on what exactly it is.

We sometimes need to remind ourselves that not everyone is at the same level. When we observe behavior low on the Ladder of Accountability by our suppliers and customers, it sticks out like such a sore thumb that we are sometimes surprised that this does not feel so blatantly wrong to them. Sometimes clients do not appreciate the level of accountability they get with us, which can be surprising, confusing, and even painful.

Managers who understand and refer to the Ladder of Accountability can identify these situations and adjust their team's approach to improve accountability. The first step is to share the Ladder with the Team. We used it as a feedback tool, and people would hear about it almost daily.

We also used it as a review tool and even a hiring tool. I tell job candidates about the importance of accountability and share some examples and real stories. Their reactions speak volumes about where they fall on the ladder. If they join in and give me some examples, they get it. If they look scared or try too hard to convince me, they are not a fit. When someone describes their other positions, their level of accountability is quite obvious. Did they complain about unfair situations, or did they always take more responsibility and make the most of any opportunity they had?

Where are you on the Ladder of Accountability? Where is your team? Let’s look more closely at each step on the Ladder of Accountability. Bear in mind that people are not stuck in place. I have never identified somebody who is and always was at the top level. Whether they are willing to move up to the next level depends entirely on how willing they are to reflect deeply and engage in the mental and emotional struggle to move up to the next level.

Level 0 – The Powerless Victim

Have you ever dealt with someone who was low on accountability? On the lowest level of accountability, the team does not get things done without the manager. I call this Level 0 because accountability is basically nonexistent. If people are happy to unload their responsibilities onto their manager, they are low on the Ladder of Accountability. These people delegate up. They are happy to lighten their own workload by giving their managers more of their work. If they have no instructions, they will wait until someone tells them what to do. If something goes wrong, they blame others. If they are not happy with something, they complain about it and leave it at that. They deny that responsibility is theirs and do what they can to avoid additional responsibility, but they will do just enough to not lose their jobs.

They can be apathetic, and they can even go beyond victimhood to be outright saboteurs. They hold grudging compliance and even malicious obedience. These are the people who will hear something a manager says to the group, secretly disagree, and later whisper in the ears of others to sabotage the effort.

Have you ever worked with someone who was highly skilled at and very comfortable with putting the monkey on their manager’s back? I once worked with someone who was technically strong but so used to the mindset of a temporary employee that the entire concept of accountability was too foreign to him. He wanted to throw everything over the wall. He was so adept at sidestepping ownership that he seemed to be refusing to move up the ladder. Finally, we had to have a discussion to give him candid feedback. He turned out to not want to increase his level of accountability. He liked where he was. It was safe, comfortable, and he had done well there in his career.

Level 1 – The Good Soldier

On the next level up, some accountability exists. Rather than wait until being told what to do, people will ask what to do and do it. Rather than deny any problems exist, the person acknowledges problems. This person is respectful but not intimidated. They conduct themselves with a professional attitude. They are responsive when addressed and reliably follow the letter of the law. When given responsibility for a task, they respond with a time expectation for when they commit to completing the task. If they cannot give the time expectation at that time, they will commit to a time when they will commit to completing a task.

When I share this with most managers, a common reaction is that they would be thrilled with a team that did this. This seems to be a high expectation for people to achieve and just get to Level 1. This is true. Level 1 requires a lot of effort to achieve, but achieving all of this is just enough to get beyond the novice level. They still have a long way to go to truly master the Ladder of Accountability.

Level 2 – The Committed Solver

At the next level the skilled practitioner no longer asks what to do, but starts to search for and recommend solutions. Now they are starting to understand how to look at things as an owner rather than as a subordinate. They take action and can handle the higher levels of pressure that come with higher levels of responsibility and uncertainty. They have become adept at removing barriers so they can navigate roadblocks. Their general attitude is, “I will do as much as I can within the existing structures.”

Can you identify the times in your development when you moved up the ladder? I recall the point when I transitioned from the You-Tell-Me-What-To-Do mindset to the I-Will-Do-All-I-Can mindset. I was at a small, microfinance organization, and we were doing an annual strategy exercise for the company, which I had always dreaded in the past. We broke up into teams and within those teams, each person had an area to focus. I was assigned innovation, and looked up what that meant and how to do it. I found myself reading about a lot of inspiring activities that other companies did. That weekend I read an entire book and several articles. As I researched more, I found more ideas, and grew more inspired. When I returned, on Monday to turn in what I had done, I hoped people were satisfied, but they were actually surprised, impressed, and excited. I came away from that experience wishing every day could be like that.

After that I stopped looking at the clock and leaving at 5 each day. I started feeling excited about thinking about work on evenings and weekends. Then I started to think about how to improve things. I started reading articles and books to get ideas on how to do things better.

Level 3 – The Indispensable Linchpin

The fully committed owner acts with more independence to implement solutions. They lead up and routinely report on their status. This person has the I’ll-Do-What-It-Takes mentality. Rather than work only within existing structures, they create the needed structures. They inspire confidence and are adept at bringing others up the Ladder of Accountability.

Once I started to look at things as an owner, I changed. Every aspect of my products became important and something I wanted to improve. I also found that I had more respect from other people. Because I cared more, I also experienced more extreme emotions. I gave up some sense of safety and the ease that comes with not being accountable. I was becoming a new person, dealing with new levels of pressure which brought out anxieties I never knew I had. In many ways, I was growing up.

So how do we implement this in our teams? First, you accept the current position of the other person. This removes emotional distractions that interfere with the learning process. Then you support the understanding. Expect to deliver the message repeatedly over the long term. Explaining the specific applications of accountability helps people connect the concepts to their own situation.

I have had to make sure I maintain humility and remind myself that everyone is at a different place in their learning journey. I was not always at the top of the Ladder of Accountability, and I still have more to learn. I tend to be very matter of fact about dealing with the Ladder of Accountability. When a situation happens, and somebody is not fully accountable, rather than initiate frustration within myself by thinking about where they should be, I just acknowledge where they are. I share with them, that this is their current level, and to go up to the next level, this is what they would do in a situation like this.

What challenges have you had with the accountability of your team? What have been your biggest difficulty in developing your own accountability?

The Three Levels of Mastery in Taking Feedback

Taking negative feedback can be a painful experience. But embracing it opens up new possibilities for learning and growth. It is a skill, and like any skill it requires practice and effort to develop.

"Your presentation sucks." Wow. That hurt. I was surprised, too. I thought my manager was going to be impressed. Did she have to say it that way? Could she have delivered the message in a better way? Sure. At that time, my initial reaction distracted me from recognizing that my presentation needed work so I could start to make it better. Years later, I know that sometimes I have to look past how people say things and find the important points in what they say. Not everyone is going to be expert at giving feedback, but I still need to be expert at taking negative feedback.

One time at the same company, we did a 360 review. When she received her review, my boss brought me into her office to say somebody commented that she curses too much. She sounded upset. She said she was upset. She asked me point blank whether I was the one who had said it. Then she said she was going to find out who said it. I never spoke to anyone else on the team about the conversation, but I was pretty sure she had the same conversation with each one of them.

This was one of the worst things she could have done. Anybody who was being honest in giving her the feedback would no longer be honest with her again. They might take a lesson from the experience and refrain from giving honest feedback to other bosses, coworkers, and maybe even other employees in the future. This lack of honesty would undermine the success of their future bosses, colleagues, employees, and companies. I do not look back and blame my former boss. The reality is that taking feedback just was not a skill she had at that time. Why would she have had that skill? She might not have even thought of taking feedback as a skill. At the time I did not see it that way either.

Only when I looked back at the incident later did I realize this happened in part because the company never gave training on how to take feedback in preparation for the 360 review. I worked at another company which did hire a consulting firm to give training on how to take feedback before administering the 360 review. However, they did not treat taking feedback as a skill. Yes, they gave us information on how to give feedback, but we cannot learn how to take feedback by listening to a lecture any more than we can learn how to ride a bike by reading a book.

We have to give feedback on the job, practice with learning activities, get expert feedback on how we gave feedback, make adjustments, and repeat. That is how we develop any skill. The only way we achieve mastery in management is, among other things, by 1) mastering the skill of taking feedback ourselves and 2) developing the people on our teams to master the skill of taking feedback. The teams who do this have an advantage over other teams. You can easily find teams and entire companies who are weak in this area. You would be hard pressed to find those who have mastered this skill.

When we hear of the importance of taking feedback, we can easily sit back and say, "Of course feedback matters." But understanding something and being really good at it are two very different things. Have you endured great struggle for years in building your taking feedback skills? If not, you can safely say you have a long way to go to master the skill of taking feedback.

At the lowest skill level of taking feedback, we get defensive. While people are giving us feedback, we interrupt them. We come up with reasons why they are wrong so we can dismiss their words and deny our own sense of vulnerability. We dispute them so we can restore our sense of superiority over them. As a result we remain stuck where we are.

Why do we avoid negative feedback? Why do we take the skill of taking feedback for granted? Are we too humbled by the possibility that we are not perfect? Is negative feedback too painful for us to endure? Are we traumatized by the possibility that we are not superior to the person giving us negative feedback? We have to ask ourselves what we lose by not getting negative feedback.

What does true mastery in the skill of getting feedback mean? You can read what I have written here about how managers of winning teams need to probe deeply to understand what is going on with the team and the impact of having a team that does not get or give feedback. Below I will share with you the three levels of mastering the skill of taking feedback.

Level 1 - Apprentice

On the first level toward mastery of getting feedback, you are more accepting of the feedback you get. Rather than defend, you ask clarifying questions to better understand the feedback. You spend time reflecting on the negative feedback.

At this stage you are uncomfortable with getting feedback, especially negative feedback. You still worry that soliciting negative feedback is a sign of weakness, but you understand that bravery cannot exist without vulnerability. You still feel the urge to slip into defensiveness, interruption, and denial, but you are aware enough to resist those temptations. The fact that this requires your full attention while you expend maximum mental and emotional effort is a sign that you are beyond your Comfort Zone and firmly in your Learning Zone.

I was interviewing a candidate for a job, and he seemed unfazed by any question I threw at him. I wanted to take him out of his Comfort Zone, so I asked him to give me some negative feedback. He told me I did not maintain full eye contact the entire time we had been speaking. I realized that he had been staring at my left eye the entire conversation. I explained that he was wrong to think that absolute eye contact is necessary. It is actually not natural. We want to find the sweet spot with eye contact -- not too much and not too little. I quickly realized I had fallen into the disputing trap. I did not lead by example in that situation. Upon reflection, I could have started by asking questions to understand why he found that I do not make enough eye contact.

Level 2 - Practitioner

On the next level up, you do not just accept and seek to understand the feedback you receive. You actively seek out feedback in general and negative feedback in particular. When you get that negative feedback, you welcome it. Your initial response is to express gratitude to the person for giving you the negative feedback. You treat negative feedback as a gift. You take it a step further and make adjustments based on that negative feedback. You practice translating negative feedback into learning goals. You may need to recruit the input of an expert to help translate those learning goals into specific practice activities.

This is where the true power starts to kick into gear. The skill of taking negative feedback introduces the awareness needed to initiate course corrections earlier and make improvements sooner. The negative feedback becomes less of a threat and more of a matter-of-fact opportunity for insight and deep reflection. Whether the person is right or wrong is less important. If somebody is thinking the negative feedback, would you rather know or be oblivious? Whatever your answer is to that question, magnify it so that the entire organization is doing the same thing. Does that work?

I once had somebody reveal to me that they were far more willing to take negative feedback from a more senior person who knew what they were talking about than from a less experienced junior-level employee. I assigned them the homework of soliciting negative feedback from a more junior-level person. This on-the-job learning activity served three purposes. First, they needed to get over their hierarchical view of who has a right to give feedback. Second, this would cultivate the feedback-giving skills in younger people. Third, this allowed them to lead by example and increase the likelihood and ability of those junior-level employees to solicit negative feedback.

Level 3 - Master

On the top level of taking feedback, you can no longer expect to just ask for negative feedback and get it. People are intentionally and actively hiding negative feedback from you. You are expert at early warning signs and probing beneath the surface to unearth negative feedback. This will naturally happen as you are more senior within the organization. People are afraid to share their negative feedback with you because the personal risk does not justify any reward they can imagine. The slightest sign of some repercussion will cause them to keep negative feedback to themselves.

You build others’ skills of giving negative feedback. You are vigilant in creating a culture where people feel safe to give negative feedback to you and to others. Kim Scott's Radical Candor is a must-read book on this subject. The times when you receive negative feedback without having to solicit it are a victory.

If what I describe sounds strange to you, it is. The culture where people freely give negative feedback is quite unique and foreign, but do not fool yourself into thinking it is impossible. Ray Dalio gave a TED Talk on how he instituted Radical Transparency at his organization. He shows how a 24-year-old employee right out of college publicly gave him, the CEO of one of the world's largest hedge funds, negative feedback. You can watch it here.

This concept is so foreign to so many companies in so many industries that it reveals tremendous opportunities. Dalio applied this to the hedge fund industry, and it translated into success in other ways. Has anyone in your industry achieved this level of mastery in taking feedback?

Where do you stand in the path toward mastering the art of taking feedback? Have you gotten feedback on your feedback-taking skills? Have you solicited feedback from someone who would make you uncomfortable? Do people only share negative feedback with you when you ask for it? Remember that during your journey toward mastery, being uncomfortable is a sign that you are in your Learning Zone.

Photo by Evan Kirby on Unsplash